Contributed by Robert Lyman © 2025. Robert Lyman’s bio can be read here.

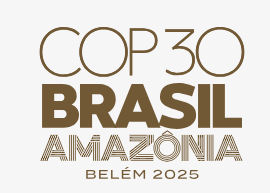

Those whose attention to the important global economic developments is focused on the near-revolution occurring in the global trading system[1],[2] and on the increasing risks related to government’s indebtedness may be forgiven if they have not paid close attention to the preparations for COP 30, the 30th Conference of the Framework Convention on Climate Change. That gathering will take place in Belem, Brazil from November 10 to 21, 2025.

Belem, Brazil – Image licensed from Adobe Stock

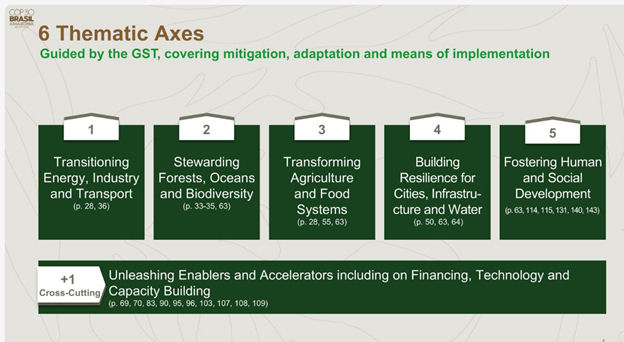

As is its custom, the United Nations holds a conference in June of each year to prepare for the following COP. This year’s conference, known as the Bonn Climate Change Conference, included the 62nd sessions of the UNFCCC Subsidiary Bodies (SB62), the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technical Advice and the Subsidiary Body for Implementation.[3],[4] The main goal of this conference was to prepare the way for the November COP by identifying the key issues that need resolution, drafting an agenda, and preparing a negotiating text including proposed policy declarations that might be the basis for consensus agreement at the Heads of State level.

While these topics are potentially of global significance, if only for the financial costs they entail, the mainstream media in most western countries provided virtually no coverage of the Bonn event. The only places in which there was broad coverage was in the reports of the non-governmental groups that depend for their existence and relevance on the funding that they receive from the UN and the governments that support the UN’s climate policy agenda.[5]

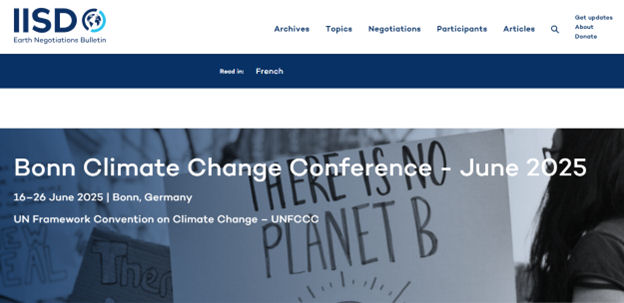

The central issues discussed at the Bonn meeting concerned the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) of the various members (including how they are to obtain funding for the next tranche of these plans to cover the period 2026-2030), the development of a framework to guide the formulation and funding of National Adaptation Plans (a new element) and how to accelerate the efforts to get the developed countries to increase their flows of grants to the developing countries, without which the developing countries will not be willing to incur the expenses of grandiose emissions reduction plans.[6],[7]

With the United States having announced that it will no longer participate in the UN’s climate efforts and therefore will not provide the several hundred billion dollars that the developing countries wanted from it, the conference might have been an opportunity for the countries to rethink the feasibility of the ambitious funding goals that were envisaged at COP 29. Instead, the developing countries “doubled-down” on their demands for more funds. They also resisted any suggestion that some of the richer “developing countries”, like China, should also contribute to climate aid.

@CartoonsbyJosh with permission

This theme was picked up by a number of non-governmental organizations that proposed ways to improve the “efficiency” of the COP process. Thus, a group of NGOs made a “united call” to end the current requirement that decisions be made by consensus and thus move to “majority-based decision making” whereby the votes to the more than one hundred developing countries would determine the nature of the UN agreements on policy and funding matters. They argued as well that the UN should cease its practice of allowing so many of the COP conferences to be hosted by major oil and producing countries (i.e. “petro-states”) that might unduly influence the outcome.

The Center for International Environmental Law[8] strongly urged the member states to place much more emphasis on environmental justice, gender justice and intersectionality. The Center insisted that “the time has come for climate negotiations to be bound by legal obligations, rather than shaped by the interests of those profiting from the status quo”. It demanded a “full phaseout of all fossil fuels without loopholes” and progress “to address the conflicts of interest and finally end the fossil fuel and other producing industries’ decades-long grip on climate negotiations.”

It will come as no surprise that the Bonn conference failed in coming up with proposed texts that could serve as the basis for advancing discussions in Brazil. It is difficult to see any circumstances in which COP 30 will be a success.

Beach time at Belem – Image licensed from Adobe Stock

[1] https://iagam.ca/insights/the-changing-landscape-of-global-trade

[2] https://www.rbc.com/en/thought-leadership/the-trade-hub/global-trade-is-being-unsettled-heres-how-canada-can-thrive-in-the-new-economic-order/

[3] https://unfccc.int/june-un-climate-meetings-2025-updates

[4] https://cop30.br/en/action-agenda

[5] https://unfccc.int/june-un-climate-meetings-2025-updates

[6] https://enb.iisd.org/sites/default/files/2025-07/enb12876e.pdf

[7] https://enb.iisd.org/bonn-climate-change-conference-sb62-sbi62-sbsta62

[8] https://www.ciel.org/news/un-climate-talks-bonn-civil-society-urges-reform-ahead-of-cop30/#:~:text=Press%20Room-,UN%20Climate%20Talks:%20Civil%20Society%20and%20Indigenous%20Peoples’%20Groups%20Urge,at%20securing%20consensus%20have%20failed.%E2%80%9D

Leave a Reply! Please be courteous and respectful; profanity will not be tolerated.